By Kimberly Wallace

In the post-war days of 1956 when people were searching for inspiration and beauty, 14-year-old Donald ‘Jackie’ Hinkson would spend hours in the Central Library on Queen’s Park East, poring over the pages of art books that contained images of impressionist paintings. For the young aspiring artist, the work of Cezanne, Degas and Monet were a feast for the eyes and food for the soul.

He never imagined that one day he would rise to prominence as Jackie Hinkson – one of T& T’s most celebrated visual artists; that articles would be written about his life and work and that he would receive an Honorary Doctorate from The UWI and a national award – the Chaconia Medal (Gold) for his contribution to the arts.

Now at the age of 80, one might think that the multidimensional artist has earned his right to lay back with a beastly cold beer and enjoy retirement at one of his favourite hangouts – Mayaro. But Hinkson, who over the decades has expanded his work to include watercolours, oils, acrylics, wood sculptures and digital art has no intention of stopping what has become like second nature. As an artist he is constantly evolving, still discovering new ways to express himself. His unquenchable desire to create art began at a young age.

‘The thought of becoming an artist never crossed my mind but I think that internally I knew it, I just never verbalised it to myself, but I felt it,’ says Hinkson at his home in St Ann’s.

Hinkson was extremely fortunate; his parents were very liberal-thinking people. While his father was a good student he never had the opportunity to further his education, so he was determined to see his six children advance themselves in any field – once it was honourable. His mother was a typical housewife who read a lot. She was a romantic at heart – a woman with a poetic side who loved learning about other countries and cultures. In retrospect, Hinkson believes his mother was secretly happy that one of her sons was pursuing art. Hinskon found out much later that she made sacrifices to ensure that he could buy a tube of paint here and there.

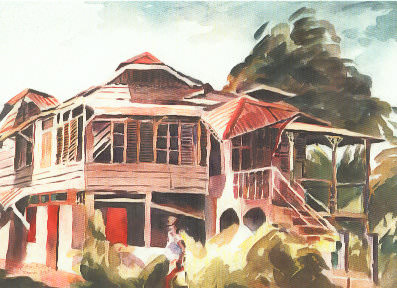

As a member of the Trinidad Art Society when the headquarters was at the old Woodbrook market on French Street, Hinkson often saw local artists the likes of Sybil Atteck, Carlisle Chang and Boscoe Holder whose works he admired but he also wanted to see the works of the international greats. The only way he could was at the library where he came across a book on the French impressionists of the 19th century who worked outdoors en plein air. Hinkson, who had been so impressed by Trinidad’s outdoor landscapes and seascapes, was stunned by the vibrancy and the way the artists captured outdoor light in their paintings. He was also astonished by English landscape watercolourists; the light and luminosity and the effect of watercolour on paper.

He was in his mid to late teens when he had a fortuitous encounter with Peter Minshall whose portrait of Hinkson hangs on one of the walls of his living room. Both men bonded over their passion for art which added impetus to their ambitions. In 1963 Hinkson

left on a one-year scholarship to study at the Academie Julian in Paris, France; his dream was to get real formal training.

‘After having seen these paintings in books – there I was, inside the Louvre, seeing, in person, the works of the men who I so admired. That was where my real education in Paris was taking place – learning and seeing these works live,’ he recalls.

Hinkson was fortunate enough to get another scholarship to do a degree in Fine Art and a diploma in Education at the University of Alberta, Canada. At that time Andy Warhol and Jackson Pollock were the talk of the town and the North American environment exposed him to international changes in the art world such as abstract expressionism, minimalism and pop art which had a lasting effect on how he saw art. There was no doubt that he would return to Trinidad – he had strong childhood roots etched in his mind of his life in Cobo town as a child and his exposure to the landscape and coconut estates while out and about with his father- a travelling officer.

After spending five years abroad, he returned to Trinidad; his goal to become a professional artist was as strong as it was when he was 14. He worked feverishly, building his repertoire and launching into landscapes and light in watercolours an experience that was accompanied with equal parts perseverance and frustration. He began teaching at his alma mater- QRC and was also determined to continue producing abstract minimalist sculptures which he discovered and fell in love with while studying in Canada. His work began to get noticed.

‘People like Nina Lamming, MP Alladin, Leo Basso and those who at the time were our leading artists were not people who got emotional and carried away. I was treated like any other artist who was obviously ambitious and I was accepted as such and they encouraged me,’ he says.

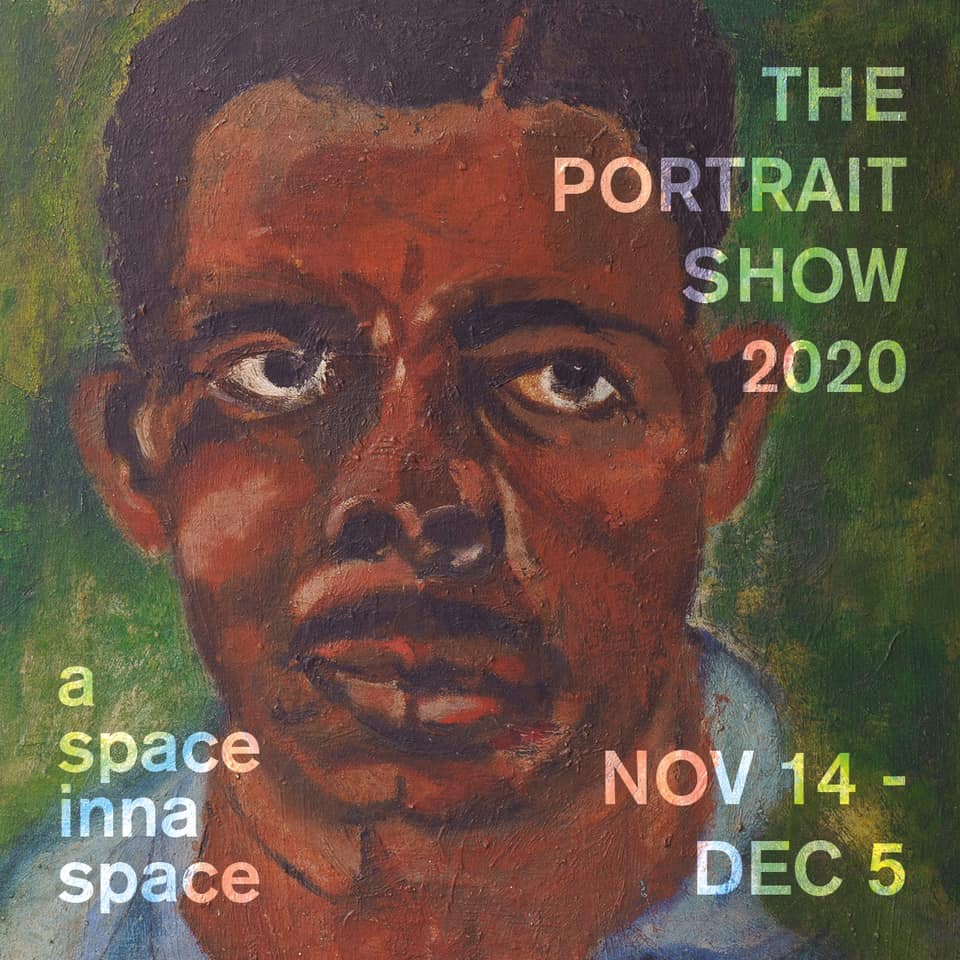

Recently Hinkson began devoting much time and effort into archiving his work, a very lengthy process which involves thousands of pieces he has done – from his earliest and smallest sketches to large mural pieces. Among his works are 150 sketch books, charcoal drawings, wood sculptures, digital art and countless drawings of landscapes and portraits, including those of his loved ones. Behind the image of the celebrated visual artist is a family man. Hinkson’s home is testament to his life’s biggest passions; art of course, and family. His walls are lined with family photos of his wife Caryl, his children Sean, David and Deborah and his grandchildren.

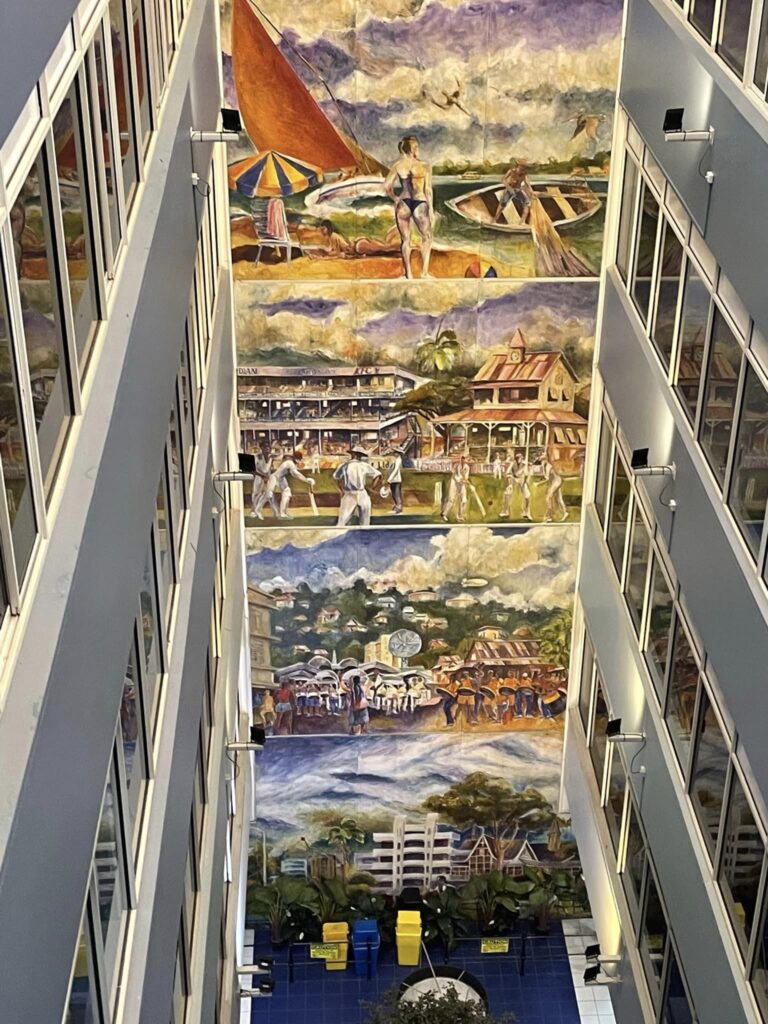

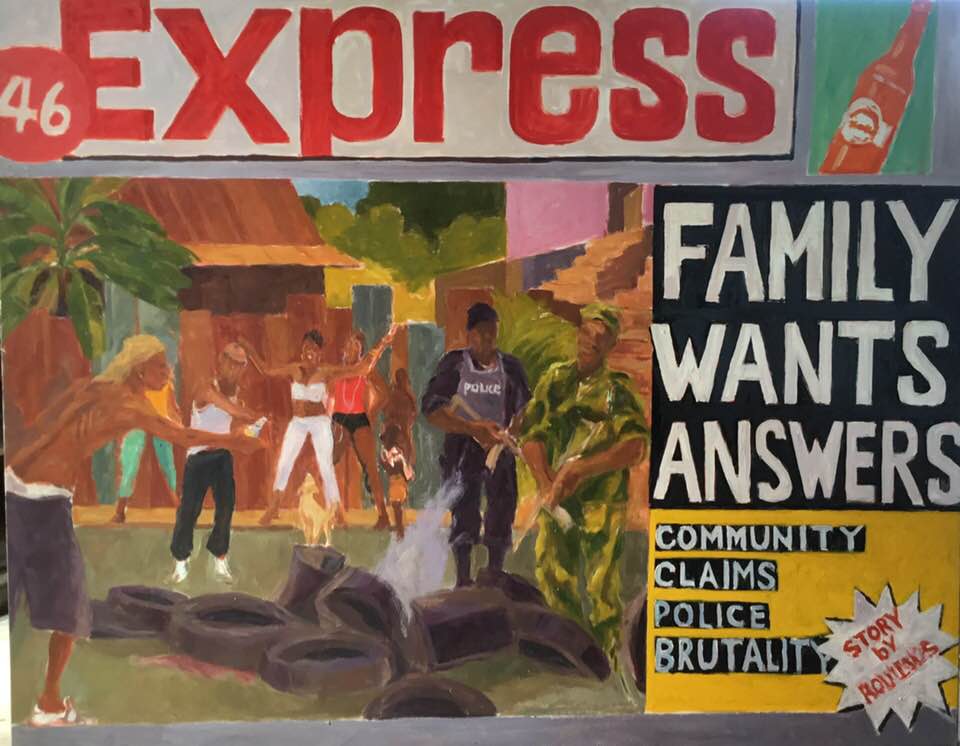

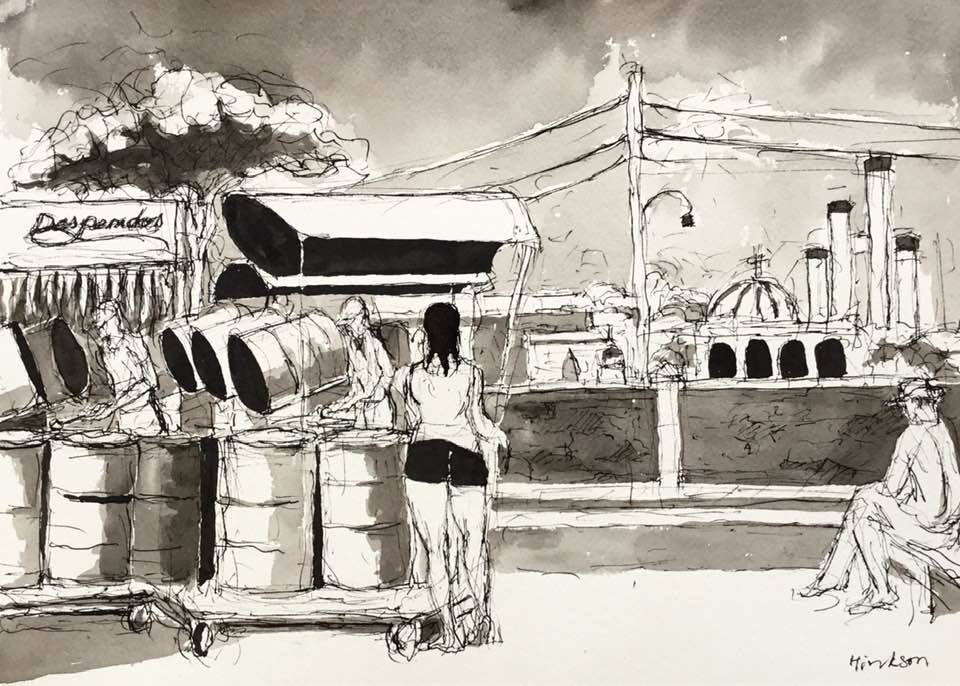

In spite of all his achievements and accolades, Hinkson has a persistent nagging conviction that he has not done as well as he could have, so his journey of exploration continues. Throughout the years Hinkson has delved into various media. He has always responded to the social, cultural, physical and political environment in order to focus on whatever dominant thought or emotion he wanted to express whether through rapid sketches, drawings of old traditional architecture and mural size works where the human figure takes on a more central role.The visual artist is currently working on a massive mural, which, once completed, would be 190 feet in length. Hinkson believes it is the responsibility of the artist to respond emotionally and intellectually to his world, to the human condition and to society and reflect the vision he has in his work.

The advancements in technology and introduction of digital art haven’t diluted creativity, it’s just another medium, says Hinkson.

The basic problem in visual expression remains the same regardless of whatever medium you use. If I’m using pencil on a piece of paper I still have to deal with line, movement, weight of tone, juxtaposition, rhythm composition and so on.

When I’m doing work on the iPad I’m very conscious that I’m dealing with the same basic problems that I had while doing an oil painting. But the technology inevitably gives it a different feel and look. There is an intensity of colours on the iPad that I can’t get with watercolours.

Over the past six decades Hinkson has risen from aspiring artist to prominence, in 2011 he was conferred with an Honorary Doctorate and he received the Chaconia Medal (Gold) in 2019. Additionally, many glowing articles have been written about him. While he doesn’t deny that artists and their contributions to society are appreciated, Hinkson laments a dismal lack of knowledge and education regarding art in general. In the 50s and 60s when the art community was a lot smaller, art was discussed and critiqued. Today, however, the reporting of art exhibitions has become less about the art and what it represents and more about frivolous details like who was at the exhibition. But for those who are interested, Hinkson is happy to share his expertise and speak with art students, encouraging them as others once encouraged him. He is very conscious that in his teen years, artists were good to him and willing to offer guidance.

It was impossible to end our interview without bringing up the subject of ‘legacy’. But Hinkson who studied the legends and became a great artist himself doesn’t give it much thought, in fact he winces when people call him an ‘icon’.

‘I would like to think that my work will be available for researchers to see and access,’ he says. ‘But as far as I’m concerned I can’t decide what my legacy should be, it’s up to the people to decide that.’