By Jarrel De Matas

Never underestimate the power of representation, especially when it comes to the silver screen. It took the death of beloved Star Trek actress Nichelle Nichols to make me realise the privilege, honour and enormous responsibility our local filmmakers have in creating stories that reflect our past and imagine the future of our nation. In this regard, Star Trek was ahead if its time, particularly when it came to imagining possible futures.

The recent passing of Nichols on July 30 at the age of 89 gives me the chance to geek out about Star Trek as well as explore the power of representation and how it can take our local film industry where no one has gone before.

The pull of Star Trek wasn’t just its futuristic technology and catchy phrases like Kirk’s ‘beam me up, Mr Scott’, Spock’s ‘Live long and prosper’, Picard’s ‘Make it so’, Janeway’s ‘Coffee, black’, or Seven of Nine’s ‘Unacceptable’. Star Trek’s emphasis on discovery and seeking out new lifeforms gave it the space to investigate complex layers of humanity.

Acting as Lieutenant Nyota Uhura, a translator and communications officer, Nichols was one of the first black women to be featured in a non-menial role on television. If the significance of a black woman among a majority white cast on television during the late 1960s is lost on you, then consider this: the US Civil Rights Act, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, colour, religion, sex or national origin, was only passed in 1964, two years before Star Trek debuted.

Nichols, the only black character in a major role, portrayed one of the most senior Starfleet officers. Her ground-breaking character didn’t stop there. As Uhura, Nichols is credited as being the first black woman to be involved in an interracial kiss on television.

Nichols understood the power of her on-screen presence and used it as a form of activism, working with NASA to help recruit more women, particularly those of colour, to its space programme.

While we may not have plans anytime soon to send Trinidadians to space, the kind of work Nichols and, by extension, Star Trek did reveals the power film has in connecting past and future experiences to help audiences imagine better futures.

Through the decades beginning from the 1950s, our film industry has highlighted provocative themes about politics, race, gender-based violence, and sexuality.

These stories may not instantly turn us into activists, but they should inspire us to live with a little more sensitivity and acceptance for one another, thereby creating a better, inclusive future for all.

In 1974, writer Raoul Pantin gave us Bim, the story of a young Indian man living in rural Chaguanas. Bim, full name Bheem Singh, endures a life of violence and abuse to emerge as leader of the opposition party. The extreme level of crime during the film-which ranges from assassination, domestic abuse, various robberies, human trafficking, rape and prostitution-reflects the darker side of a nation attempting to find its way in the immediate post-Independence era.

Added to the spiralling crime problem are the racial prejudices experienced by Bim when he goes to live with his aunt and her Afro-Trinidadian husband, Balo, in Belmont. Almost a half-century later, Pantin’s sociopoliti cal commentary through Bim remains pertinent to our current reality. The level of racial conflict mixed with political aspirations that Pantin portrays now seems ominous for the ways in which they have persisted. If Pantin intended on showing us what our future would be like and therefore rousing us to take action, we didn’t quite heed the call.

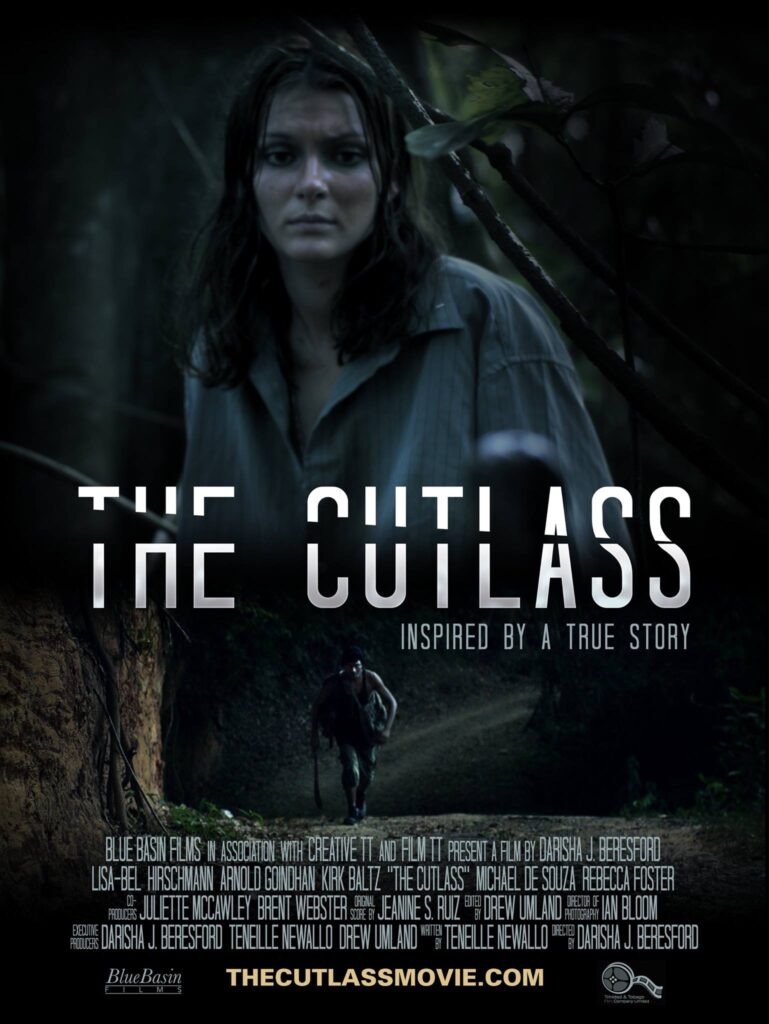

More recently, movies such as Play the Devil (2016) and The Cutlass (2017) highlight themes related to homosexuality and gender-based violence. Following global trends in human rights activism such as the #MeToo movement and LGBTQ equality, both movies take on even greater significance because they are rooted in Trinidadian experiences.

Play the Devil uniquely brings together elements of Carnival with same-sex desire. Maria Govan’s film follows 18-year-old Greg and his affair with James, an older, married businessman. Although the film trades a positive portrayal of homosexuality for a tense and dark ending, Play the Devil was a pivotal film and socio-cultural moment for T& T because it featured not just two men, but two Trinidadian men, in an intimate relationship. In the psychological thriller The Cutlass, Teneille Newallo drew on her personal experience of losing a friend to violence to contribute to the Say No to Violence Against Women movement.

Newallo explained in an interview that the film was meant to reflect a different kind of kidnapper, unlike the ones responsible for kidnappings during 2005, one who was intelligent, calm, brave, focused and calculating. The Cutlass is true to form because in 2005 Trinidad was believed to have the second highest kidnapping rate after Colombia. Newallo’s focus on a particularly dark time in our nation’s modern history is eerily entertaining, though less so when more recent kidnappings, and murders, of Ashanti Riley and Andrea Bharatt are remembered.

If we consider these films as measurements of how far we have progressed as a nation, things do not seem very uplifting.

Like Nichelle Nichols and Star Trek, our local film industry has the potential to not only envision, but also inspire us to create a future where everyone has the right to aspire and achieve.

Jarrel De Matas is is a PhD candidate and teaching associate, Dept of English, College of Humanities and Fine Arts, University of Massachusetts, Amherst